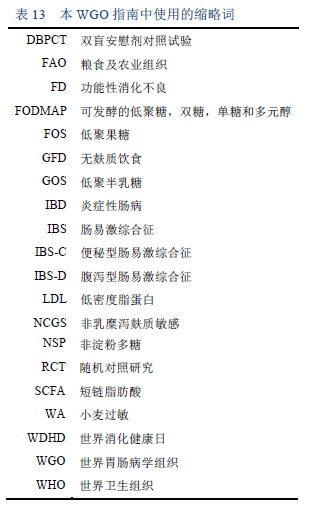

6.1 缩略词

6.2 各组织发布的相关指南

· 世界卫生组织(WHO)营养指南 [105]

www.who.int/publications/guidelines/nutrition/en/

· 美国胃肠病学会(ACG)指南(例如,成人住院患者的营养治疗)[106]

https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.28

· 英国胃肠病学会(BSG)指南(例如,乳糜泻)[107]

https://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical/bsg-guidelines.html

http://gut.bmj.com/content/63/8/1210

· 国家健康和护理卓越研究所(NICE)指南(例如,饮食,营养和肥胖)[108]

www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/lifestyle-and-wellbeing/diet--nutrition-and-obesity

· 北美/欧洲儿科胃肠病学,肝脏病学和营养学(NASPGHAN / ESPGHAN)指南(儿童) [109] www.naspghan.org/content/55/en/Nutrition-and-Obesity

世界胃肠病学组织(WGO)指南:应对常见的胃肠道症状(Hunt et al, 2014) [19]

https://journals.lww.com/jcge/Fulltext/2014/08000/Coping_With_Common_Gastrointestinal_Symptoms_in.4.aspx

http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/common-gi-symptoms

· 世界胃肠病学组织(WGO)关于乳糜泻的指南 (Bai and Ciacci, 2017) [2]

http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/celiac-disease

· 英国饮食协会(BDA):成人肠易激综合征的饮食管理(McKenzie et al., 2016)[22]

https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12385

6.3

1. Bai JC, Ciacci C, Corazza GR, Fried M, Olano C, Rostami-Nejad M, et al. Celiac disease. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines [Internet]. Milwaukee, WI: World Gastroenterology Organisation; 2016 [cited 2017 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/celiac-disease/celiac-disease-english

2. Bai JC, Ciacci C. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines: celiac disease. February 2017. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):755–68.

3. Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH, Ferreri S, Knudtson M, Koraym A, et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(4):188–205.

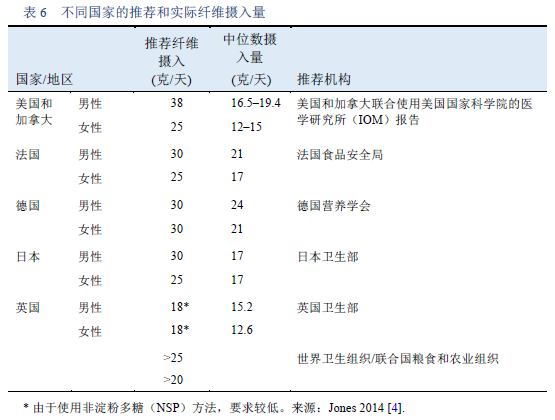

4. Jones JM. CODEX-aligned dietary fiber definitions help to bridge the “fiber gap.” Nutr J. 2014;13:34.

5. Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(10):1716–31.

6. Kim Y, Je Y. Dietary fiber intake and total mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(6):565–73.

7. Threapleton DE, Greenwood DC, Evans CEL, Cleghorn CL, Nykjaer C, Woodhead C, et al. Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6879.

8. Yang Y, Zhao L-G, Wu Q-J, Ma X, Xiang Y-B. Association between dietary fiber and lower risk of all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(2):83–91.

9. Yao B, Fang H, Xu W, Yan Y, Xu H, Liu Y, et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose-response analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(2):79–88.

10. American Association of Cereal Chemists. The definition of dietary fiber. Report of the Dietary Fiber Definition Committee to the Board of Directors of the American Association Of Cereal Chemists. Submitted January 10, 2001. Cereal Foods World. 2001;46(3):112–26.

11. Livingston KA, Chung M, Sawicki CM, Lyle BJ, Wang DD, Roberts SB, et al. Development of a publicly available, comprehensive database of fiber and health outcomes: rationale and methods. PloS One. 2016;11(6):e0156961.

12. Howlett JF, Betteridge VA, Champ M, Craig SAS, Meheust A, Jones JM. The definition of dietary fiber – discussions at the Ninth Vahouny Fiber Symposium: building scientific agreement. Food Nutr Res [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Jan 15];54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2972185/

13. McRorie JW, McKeown NM. Understanding the physics of functional fibers in the gastrointestinal tract: an evidence-based approach to resolving enduring misconceptions about insoluble and soluble fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(2):251–64.

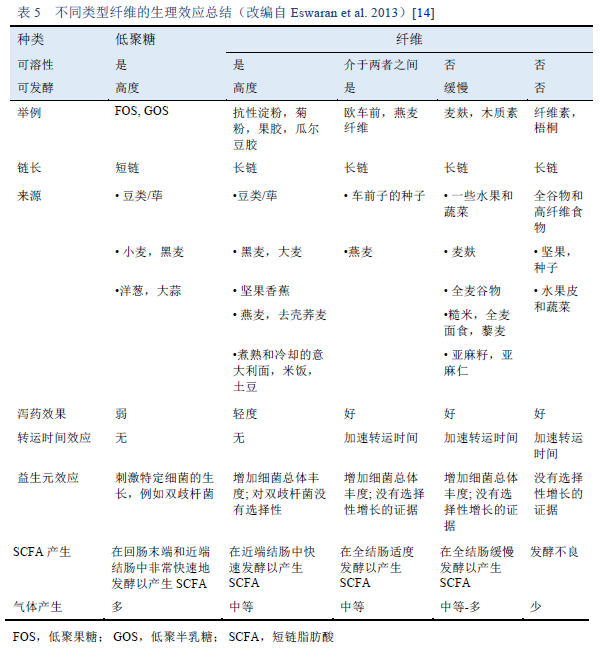

14. Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey WD. Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):718–27.

15. Maslowski KM, Mackay CR. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(1):5–9.

16. Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417–35.

17. Christodoulides S, Dimidi E, Fragkos KC, Farmer AD, Whelan K, Scott SM. Systematic review with meta-analysis: effect of fibre supplementation on chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(2):103–16.

18. Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, Thomsen OO, Fernandez LB, Garisch J, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: Constipation--a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(6):483–7.

19. Hunt R, Quigley E, Abbas Z, Eliakim A, Emmanuel A, Goh K-L, et al. Coping with common gastrointestinal symptoms in the community: a global perspective on heartburn, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain/discomfort May 2013. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):567–78.

20. Rao SSC, Patcharatrakul T. Diagnosis and treatment of dyssynergic defecation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423–35.

21. Suares NC, Ford AC. Systematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(8):895–901.

22. McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H, Gulia P, Horobin J, O’Sullivan NA, et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(5):549–75.

23. Nagarajan N, Morden A, Bischof D, King EA, Kosztowski M, Wick EC, et al. The role of fiber supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Sep;27(9):1002–10.

24. Wedlake L, Slack N, Andreyev HJN, Whelan K. Fiber in the treatment and maintenance of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):576–86.

25. Gibson PR. Use of the low-FODMAP diet in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:40–2.

26. Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3(1):8–14.

27. Böhm SK. Risk factors for diverticulosis, diverticulitis, diverticular perforation, and bleeding: a plea for more subtle history taking. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31(2):84–94.

28. Carabotti M, Annibale B, Severi C, Lahner E. Role of fiber in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2017;9(2):161.

29. Asano T, McLeod RS. Dietary fibre for the prevention of colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD003430.

30. Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P, Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Skeie G, et al. Dietary fibre intake and risks of cancers of the colon and rectum in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). PloS One. 2012;7(6):e39361.

31. Yao Y, Suo T, Andersson R, Cao Y, Wang C, Lu J, et al. Dietary fibre for the prevention of recurrent colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 8;1:CD003430.

32. Vanhauwaert E, Matthys C, Verdonck L, Preter VD. Low-residue and low-fiber diets in gastrointestinal disease management. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):820–7.

33. Butt J, Bunn C, Paul E, Gibson P, Brown G. The White Diet is preferred, better tolerated, and non-inferior to a clear-fluid diet for bowel preparation: A randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb;31(2):355–63.

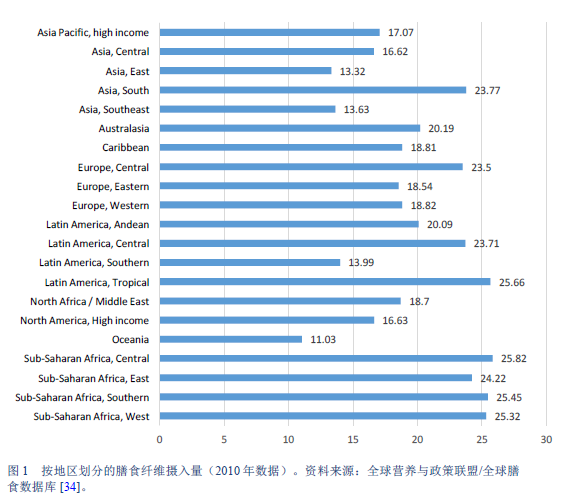

34. Global Nutrition and Policy Consortium. Dietary intake of major foods by region, 1990 [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.globaldietarydatabase.org/dietary-data-by-region.html

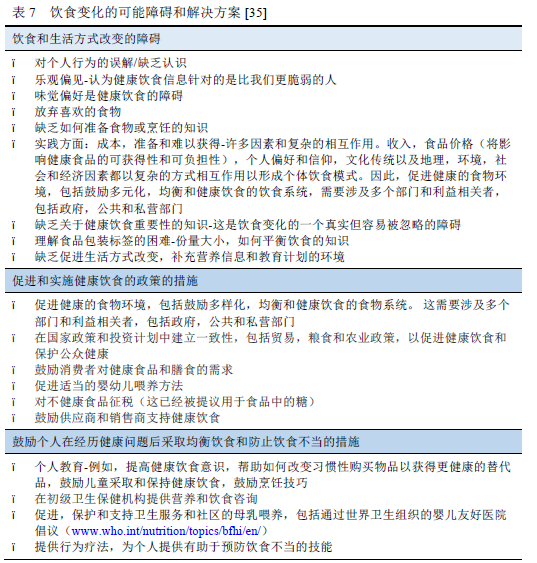

35. World Health Organization. Healthy diet [Internet]. WHO. 2017 [cited 2017 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs394/en/

36. United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service. USDA food composition databases [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 21]. Available from: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/index

37. European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Why we eat what we eat: the barriers to dietary and lifestyle change [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2018 May 19]. Available from: http://www.eufic.org/en/healthy-living/article/why-we-eat-what-we-eat-the-barriers-to-dietary-and-lifestyle-change

38. Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(8):1366–73.

39. Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, Irving PM, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(8):874–82.

40. Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67-75.e5.

41. Eswaran SL, Chey WD, Han-Markey T, Ball S, Jackson K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the low FODMAP diet vs. modified NICE guidelines in US adults with IBS-D. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1824–32.

42. Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Anderson JL, Barrett JS, Muir JG, Irving PM, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142(8):1510–8.

43. McIntosh K, Reed DE, Schneider T, Dang F, Keshteli AH, De Palma G, et al. FODMAPs alter symptoms and the metabolome of patients with IBS: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2016;66(7):1241–51.

44. de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, Batman B, O’Brien LA, Leeper JA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(9):895–903.

45. Pedersen N, Vegh Z, Burisch J, Jensen L, Ankersen DV, Felding M, et al. Ehealth monitoring in irritable bowel syndrome patients treated with low fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6680–4.

46. Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, Costigan C, Cox E, Lam C, et al. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(1):110–9.

47. Major G, Pritchard S, Murray K, Alappadan JP, Hoad CL, Marciani L, et al. Colon hypersensitivity to distension, rather than excessive gas production, produces carbohydrate-related symptoms in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):124-133.e2.

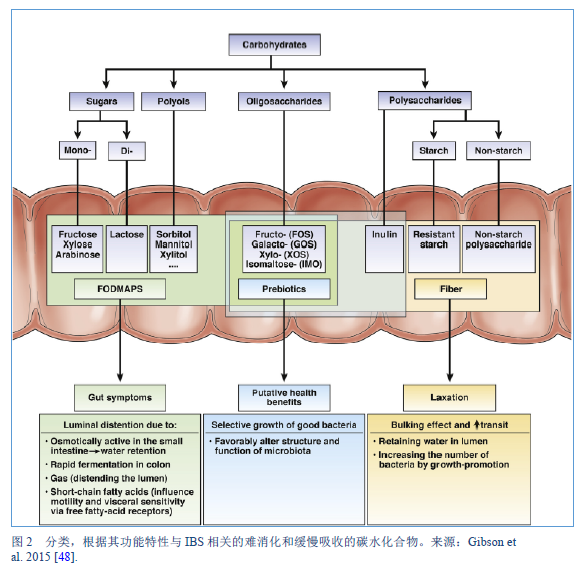

48. Gibson PR, Varney J, Malakar S, Muir JG. Food components and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1158-1174.e4.

49. Muir JG, Shepherd SJ, Rosella O, Rose R, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55(16):6619–27.

50. Muir JG, Rose R, Rosella O, Liels K, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, et al. Measurement of short-chain carbohydrates in common Australian vegetables and fruits by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(2):554–65.

51. Biesiekierski JR, Rosella O, Rose R, Liels K, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, et al. Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosacharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(2):154–76.

52. Yao CK, Tan H-L, van Langenberg DR, Barrett JS, Rose R, Liels K, et al. Dietary sorbitol and mannitol: food content and distinct absorption patterns between healthy individuals and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27 Suppl 2:263–75.

53. Monash University. Download the low FODMAP diet app for on-the-go IBS support [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.med.monash.edu/cecs/gastro/fodmap/iphone-app.html

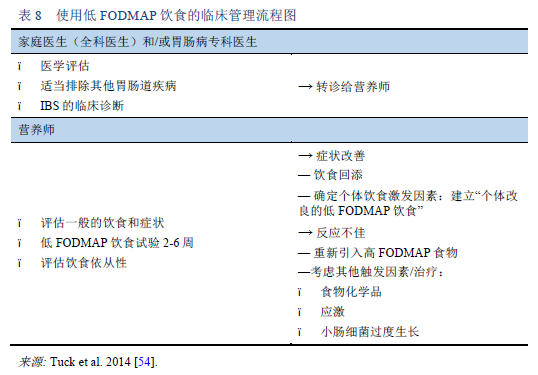

54. Tuck CJ, Muir JG, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols: role in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8(7):819–34.

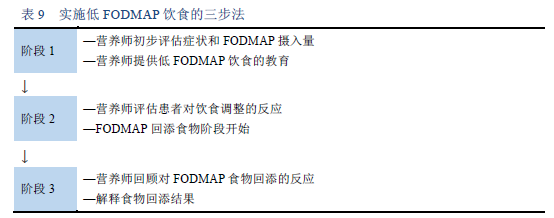

55. Barrett JS. How to institute the low-FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:8–10.

56. Tuck C, Barrett J. Re-challenging FODMAPs: the low FODMAP diet phase two. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:11–5.

57. McMeans AR, King KL, Chumpitazi BP. Low FODMAP dietary food lists are often discordant. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(4):655–6.

58. Barrett JS. Extending our knowledge of fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates for managing gastrointestinal symptoms. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28(3):300–6.

59. Payne AN, Chassard C, Lacroix C. Gut microbial adaptation to dietary consumption of fructose, artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols: implications for host-microbe interactions contributing to obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13(9):799–809.

60. Staudacher HM. Nutritional, microbiological and psychosocial implications of the low FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:16–9.

61. Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(6):1382–90.

62. Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Farquharson FM, Louis P, Fava F, Franciosi E, et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and a probiotic restores bifidobacterium species: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(4):936–47.

63. Prince AC, Myers CE, Joyce T, Irving P, Lomer M, Whelan K. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in clinical practice improves functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1129–36.

64. Moore JS, Gibson PR, Perry RE, Burgell RE. Endometriosis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: specific symptomatic and demographic profile, and response to the low FODMAP diet. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(2):201–5.

65. Iacovou M, Mulcahy EC, Truby H, Barrett JS, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Reducing the maternal dietary intake of indigestible and slowly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates is associated with improved infantile colic: a proof-of-concept study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;31(2):256–65.

66. Marum AP, Moreira C, Saraiva F, Tomas-Carus P, Sousa-Guerreiro C. A low fermentable oligo-di-mono saccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet reduced pain and improved daily life in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Pain. 2016;13:166–72.

67. Tan VP. The low-FODMAP diet in the management of functional dyspepsia in East and Southeast Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:46–52.

68. Shaukat A, Levitt MD, Taylor BC, MacDonald R, Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, et al. Systematic review: effective management strategies for lactose intolerance. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):797–803.

69. Lomer MCE, Parkes GC, Sanderson JD. Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice – myths and realities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(2):93–103.

70. Itan Y, Jones BL, Ingram CJ, Swallow DM, Thomas MG. A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:36.

71. Matthews SB, Waud JP, Roberts AG, Campbell AK. Systemic lactose intolerance: a new perspective on an old problem. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(953):167–73.

72. Crittenden RG, Bennett LE. Cow’s milk allergy: a complex disorder. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(6 Suppl):582S-91S.

73. Zhu Y, Zheng X, Cong Y, Chu H, Fried M, Dai N, et al. Bloating and distention in irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gas production and visceral sensation after lactose ingestion in a population with lactase deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1516–25.

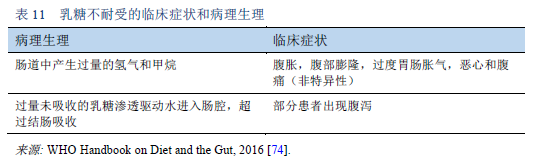

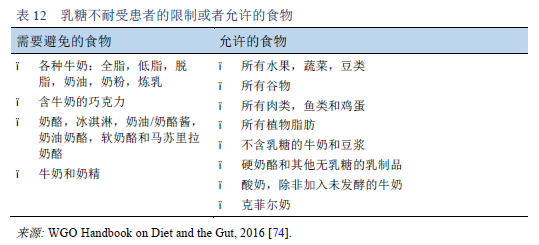

74. World Gastroenterology Organisation. WGO handbook on diet and the gut. World Digestive Health Day WDHD — May 29, 2016 [Internet]. Makharia GK, Sanders DS, editors. Milwaukee, WI: World Gastroenterology Organisation and WGO Foundation; 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 24]. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/WGOHandbookonDietandtheGut_2016_Final.pdf

75. O’Connell S, Walsh G. Physicochemical characteristics of commercial lactases relevant to their application in the alleviation of lactose intolerance. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2006;134(2):179–91.

76. Montalto M, Nucera G, Santoro L, Curigliano V, Vastola M, Covino M, et al. Effect of exogenous beta-galactosidase in patients with lactose malabsorption and intolerance: a crossover double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(4):489–93.

77. Lin MY, Dipalma JA, Martini MC, Gross CJ, Harlander SK, Savaiano DA. Comparative effects of exogenous lactase (beta-galactosidase) preparations on in vivo lactose digestion. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38(11):2022–7.

78. Rosado JL, Solomons NW, Lisker R, Bourges H. Enzyme replacement therapy for primary adult lactase deficiency. Effective reduction of lactose malabsorption and milk intolerance by direct addition of beta-galactosidase to milk at mealtime. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(5):1072–82.

79. Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructose and lactose testing. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(5):293–6.

80. Yao CK, Tuck CJ, Barrett JS, Canale KE, Philpott HL, Gibson PR. Poor reproducibility of breath hydrogen testing: Implications for its application in functional bowel disorders. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(2):284–92.

81. Marriott BP, Cole N, Lee E. National estimates of dietary fructose intake increased from 1977 to 2004 in the United States. J Nutr. 2009;139(6):1228S-1235S.

82. Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MCE. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(5):487–95.

83. Henström M, Diekmann L, Bonfiglio F, Hadizadeh F, Kuech E-M, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, et al. Functional variants in the sucrase–isomaltase gene associate with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2018;67:263–70.

84. Cohen SA. The clinical consequences of sucrase–isomaltase deficiency. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2016;3(1):5.

85. Puntis JWL, Zamvar V. Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency: diagnostic challenges and response to enzyme replacement therapy. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(9):869–71.

86. Harms H-K, Bertele-Harms R-M, Bruer-Kleis D. Enzyme-substitution therapy with the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in congenital sucrase–isomaltase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(21):1306–9.

87. Portincasa P, Bonfrate L, de Bari O, Lembo A, Ballou S. Irritable bowel syndrome and diet. Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;5(1):11–9.

88. Ford AC, Vandvik PO. Irritable bowel syndrome: dietary interventions. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015;2015:pii: 0410.

89. Bhat K, Harper A, Gorard DA. Perceived food and drug allergies in functional and organic gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(5):969–73.

90. Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome — etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(5):667–72.

91. Lacy BE. The science, evidence, and practice of dietary interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(11):1899–906.

92. Harvie RM, Chisholm AW, Bisanz JE, Burton JP, Herbison P, Schultz K, et al. Long-term irritable bowel syndrome symptom control with reintroduction of selected FODMAPs. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(25):4632–43.

93. World Gastroenterology Organisation. Global guidelines [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 May 19]. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines

94. Quigley EMM, Fried M, Gwee K-A, Khalif I, Hungin APS, Lindberg G, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines. Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective. Update September 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(9):704–13.

95. Shahbazkhani B, Sadeghi A, Malekzadeh R, Khatavi F, Etemadi M, Kalantri E, et al. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity has narrowed the spectrum of irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4542–54.

96. Eswaran S, Goel A, Chey WD. What role does wheat play in the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;9(2):85–91.

97. Barmeyer C, Schumann M, Meyer T, Zielinski C, Zuberbier T, Siegmund B, et al. Long-term response to gluten-free diet as evidence for non-celiac wheat sensitivity in one third of patients with diarrhea-dominant and mixed-type irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(1):29–39.

98. Aziz I, Trott N, Briggs R, North JR, Hadjivassiliou M, Sanders DS. Efficacy of a gluten-free diet in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome–diarrhea unaware of their HLA-DQ2/8 genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(5):696-703.e1.

99. Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, Soresi M, D’Alcamo A, Cavataio F, et al. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(12):1898–906.

100. Carroccio A, D’Alcamo A, Iacono G, Soresi M, Iacobucci R, Arini A, et al. Persistence of nonceliac wheat sensitivity, based on long-term follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):56-58.e3.

101. Skodje GI, Sarna VK, Minelle IH, Rolfsen KL, Muir JG, Gibson PR, et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):529-539.e2.

102. Gibson PR, Skodje GI, Lundin KEA. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:86–9.

103. Molina-Infante J, Carroccio A. Suspected nonceliac gluten sensitivity confirmed in few patients after gluten challenge in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(3):339–48.

104. Moayyedi P, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al. The effect of dietary intervention on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6(8):e107.

105. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on nutrition [Internet]. WHO. 2018 [cited 2017 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/nutrition/en/

106. McClave SA, DiBaise JK, Mullin GE, Martindale RG. ACG clinical guideline: nutrition therapy in the adult hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(3):315–34.

107. Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63(8):1210–28.

108. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Diet, nutrition and obesity [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 May 19]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/resources/lifestyle-and-wellbeing/diet--nutrition-and-obesity

109. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). Nutrition & obesity [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 May 19]. Available from: http://www.naspghan.org/content/55/en/Nutrition-and-Obesity